As a nonprofit leader, you’re no stranger to having to make the most of your limited resources. While maximized fundraising seems like the solution, the truth is that it takes responsible allocation of your resources to make sure every dollar is used wisely—and this starts with effective documentation.

As a nonprofit leader, you’re no stranger to having to make the most of your limited resources. While maximized fundraising seems like the solution, the truth is that it takes responsible allocation of your resources to make sure every dollar is used wisely—and this starts with effective documentation.

A chart of accounts (COA) is the foundation for all financial reporting. It is a list that details your nonprofit’s financial accounts to organize your most essential financial data. When well-structured, this document can help you accurately track your income and expenses to streamline budgeting and financial reporting.

In this guide, we’ll explore the basics of creating and managing a nonprofit COA, starting with three simple steps you can take to develop this document.

3 Steps to Create a Chart of Accounts

When it comes to creating your nonprofit’s COA, there are generally three steps you’ll need to follow:

- Decide how you’ll categorize financial data. Most COAs are organized into five categories: assets, liability, net assets, revenue, and expense accounts. Then, those accounts are further divided into subcategories. For example, assets may be broken down into cash, savings, investments, and accounts receivable. While you can use any subcategories that align with your organization’s unique financial situation, try to keep your list concise. According to Chazin & Company, the biggest mistake nonprofits make is creating too many accounts, which yields confusing results.

- Choose a numbering convention. Each category and subcategory is labeled according to the number it has been assigned in a COA. For example, assets usually start with 1. That means petty cash may be 1100, equipment may be 1200, property your nonprofit owns may be 1300, and so on. Liabilities usually start with 2, net assets with 3, revenue with 4, and expenses with 5 and beyond.

- Provide a column for additional notes. While your nonprofit should be careful not to overload its COA with too many categories, you also must provide enough detail to accurately reflect your financial activity. Add an extra column in your spreadsheet for additional notes where you can record important details about each list item, such as donor restrictions on income.

Remember to consider how each category impacts your nonprofit’s financial decision-making. For example, when listing liabilities, do you need to separate every single type of payroll withholding into separate subcategories or can you aggregate them into one or two?

Once you’ve developed the structure of the COA, all that’s left is to fill it in with your nonprofit’s financial data.

Example of a Nonprofit COA

To visualize how your nonprofit might break down its list into categories and subcategories using a specific numbering convention, here is an example you can follow:

Assets (1000)

- 1100: Petty Cash

- 1200: Accounts receivable

- 1300: Equipment

- 1400: Property

- 1500: Petty cash

- 1600: Investments

Liabilities (2000)

- 2100: Accounts payable

- 2200: Accrued salaries

- 2300: Line of credit

- 2400: Loans

Net assets (3000)

- 3100: Unrestricted funds

- 3200: Temporarily restricted funds

- 3300: Permanently restricted funds

Revenue (4000)

- 4100: Individual donations

- 4200: Federal grants

- 4300: In-kind contributions

- 4400: Foundation grants

Expenses (5000)

- 5100: Salaries

- 5110: Payroll taxes

- 5120: Health Insurance

- 5200: Rent

- 5300: Utilities

3 Tips for Managing Your COA

Creating a COA is not a one-and-done process. Instead, you should continuously reference and update this document to ensure it reflects up-to-date financial information. Use the following tips to maintain your COA.

1. Work With a Nonprofit Accountant.

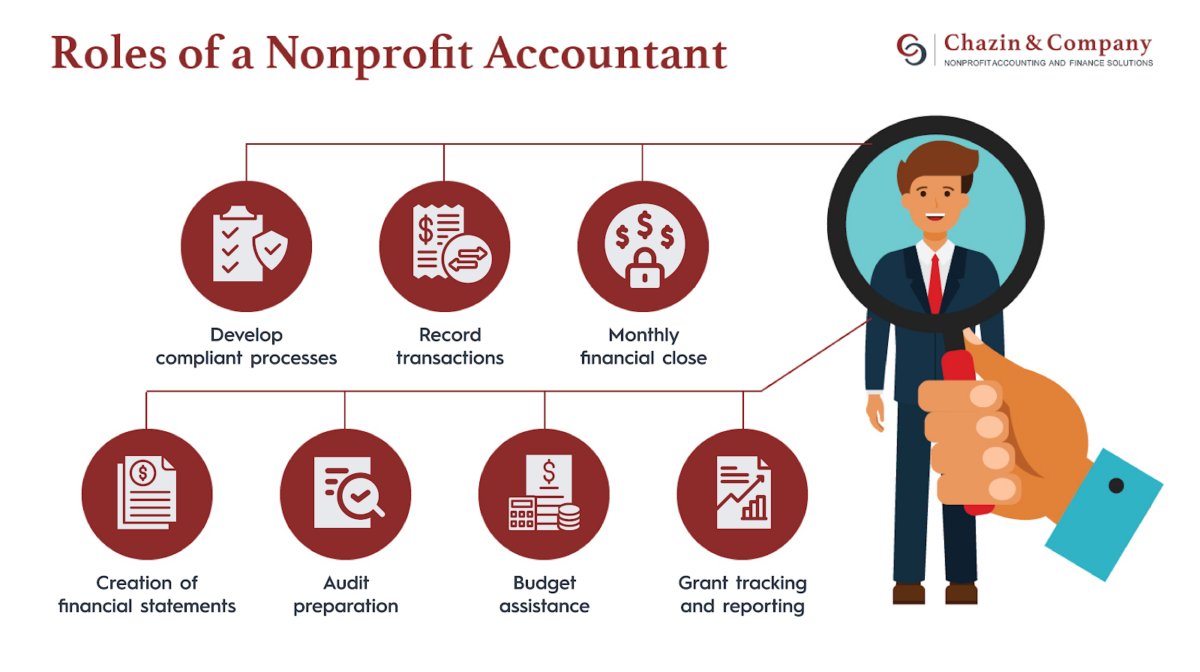

When handling your nonprofit’s finances in any capacity, a professional’s expertise is always your best bet for getting it right. A nonprofit accountant has in-depth knowledge of the unique financial issues facing nonprofits to help construct an effective COA. Because nonprofit accounting is held to specific standards such as the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), this expertise is vital to ensure your COA is accurate, useful, and will hold up to audit scrutiny.

To find a qualified candidate, look for a professional who has worked extensively with nonprofits of similar sizes and in similar verticals to yours. You can use case studies and client testimonials to learn about other organizations’ experiences working with the candidate.

Also, remember to look at the bigger picture: What roles do you expect the accountant to fill outside of helping with your COA? Choose an experienced nonprofit accountant who fills the following roles:

- Develop compliant processes

- Record transactions

- Monthly financial close

- Creation of financial statements

- Audit preparation

- Budget assistance

- Grant tracking and reporting

A nonprofit accountant who checks all of these boxes will be able to help your nonprofit not just craft an effective COA, but manage its finances for efficient reporting, budgeting, and risk management.

2.Take an Organized Approach.

Just as your nonprofit must organize details and logistics when planning fundraisers, you’ll also need an organized approach to creating a COA. This involves:

- Removing unused accounts: Let’s say your nonprofit includes a category in its COA for federal grants, but you realize three years later that you haven’t applied for any. This category would unnecessarily clutter your COA and provide no value when looking through your financial data, so you should inactivate it and any other unused accounts.

- Standardizing data entry: Especially if numerous team members interact with your COA, you’ll need a standardized process for entering data to maintain consistency and ensure more meaningful financial reporting. According to NPOInfo’s guide to nonprofit data hygiene, this includes setting rules for how data should be formatted and how errors should be handled.

- Grouping accounts where possible: To keep an organized and concise list of accounts, consider grouping relevant subcategories. For example, expenses such as employees’ healthcare and retirement benefits might be easily combined into a parent category called “employee benefits” or separate utilities such as water, trash, electricity, and gas might be easily grouped into a parent category called utilities.

Train your team on data hygiene best practices to ensure everyone who edits your COA follows the same standards. Hygienic data will also help your nonprofit maintain accurate records so that you can complete important tax filings, like Form 990, without issue.

3. Audit Your COA Over Time.

As your nonprofit’s financial situation and needs evolve over time, so should your COA. Make sure your chart is easy to edit so your team can add, remove, and change categories over time as needed.

Regularly review your chart to ensure all transactions are recorded properly and that each account is appropriately categorized. Set a regular schedule for these audits to systematically check for errors every month, quarter, or year, depending on which frequency makes the most sense for your organization.

The Bottom Line

Whether you’re recording major gifts, marketing costs, or investment returns, a nonprofit COA is the key to getting your financial records in order. Research nonprofit accountants to find a professional who is best suited to meet your organization’s needs and talk to them about getting started with a COA.

About the Author

Jackie McLaughlin, CPA, Quality Control and Learning Manager at Chazin & Company

Jackie McLaughlin, CPA, Quality Control and Learning Manager at Chazin & Company

Jackie is a seasoned accounting professional with over 35 years of accounting experience, 18 years specific to nonprofit accounting. She started her career as an auditor with KPMG where her client base consisted of tech startups. From there, she worked for Fortune 500 companies in audit management and internal audit.

Returning to her passion for startups, Jackie has since dedicated her training and expertise to the nonprofit sector. She is currently responsible for quality control, training, and financial reviews, through which she helps nonprofits achieve financial integrity and operational excellence.